Written by Marlon Bäumer and Carolin Gluchowski

Meet Margarete, the protagonist of our graphic novel “Breaking Walls.” In 1522, she entered the Cistercian convent of Wienhausen, where she would spend her life amid one of the most turbulent chapters of the convent’s history.

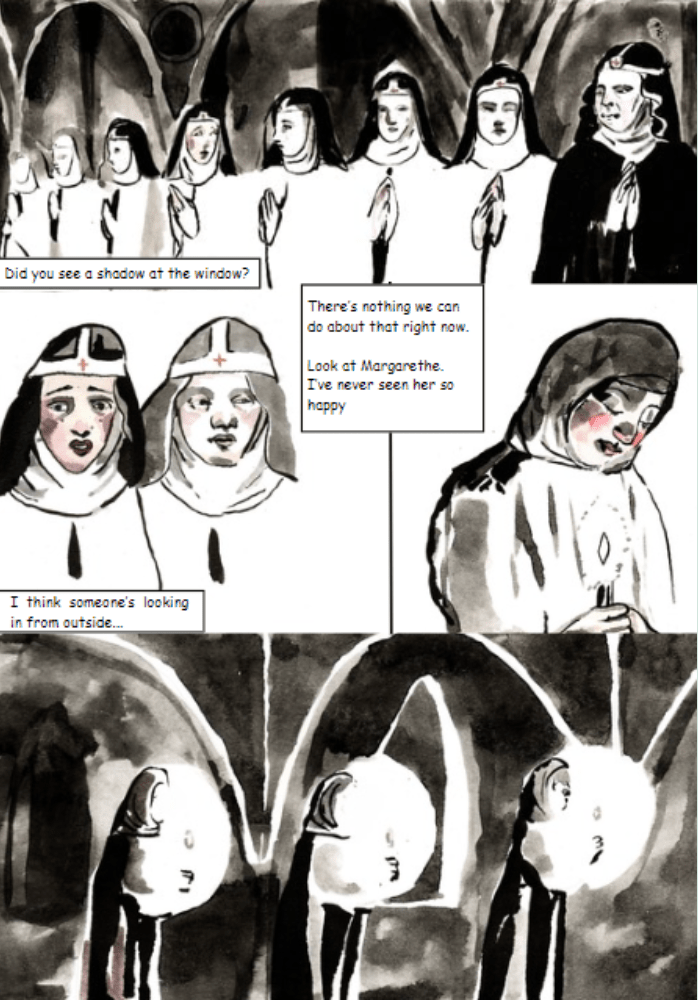

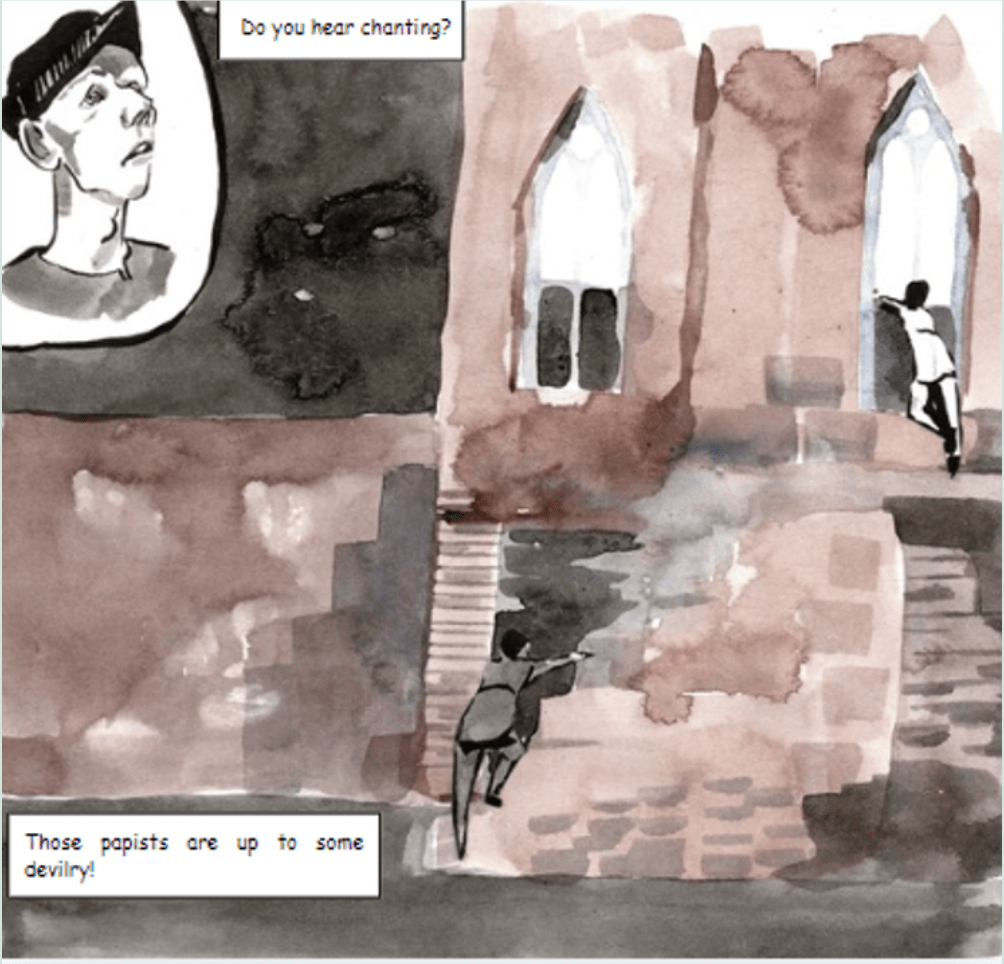

When Margarethe (von dem) Stove was finally able to make her profession in the convent of Wienhausen in the 1530s and be consecrated as a bride of Christ, it happened – as the convent chronicle reports – under extraordinary circumstances: “When the time came for Margarethe Stove to finally accept the order together with the others, she was presented to the then Domina, Catharina Remstede, on the Wednesday after Pentecost. Before her, she took the vow of eternal obedience. On the following Sunday, she was finally fully consecrated and clothed, by Mr. H. B., who represented the Abbot of Riddagshausen. However, they had to perform the singing and reading in a muted voice, as Lutherans lived in the area (by that time, the convent was no longer well-protected, as a quarter of it had been torn down, allowing anyone to enter without much difficulty). One of these Lutherans was even so brazen as to climb through a choir window to observe what they were doing.“

The Wienhausen convent chronicle leaves no doubt: Margarethe’s profession had to take place in semi-secrecy. The singing and reading of the old-faith nuns, as well as the ringing of the bells –elements of the traditional soundscape of the convent – evidently aroused the ire of the Lutheran neighbors. However, the precautions the nuns took to protect themselves had only limited success. Due to the partially destroyed convent buildings and damaged enclosure barriers, a Lutheran was even able to witness Margarethe’s profession – a profoundly intimate and emotional moment in the young woman’s life – by climbing through a window, thereby symbolically breaching the enclosure. Instead of the Abbot of Riddagshausen, another, unnamed but presumably lower-ranking old-faith cleric carried out the consecration (and likely the crowning) of the new choir nun. The text vividly illustrates the extent to which the Reformation under Duke Ernst affected the convent space and the religious practices of the nuns and how the convents resisted these changes.

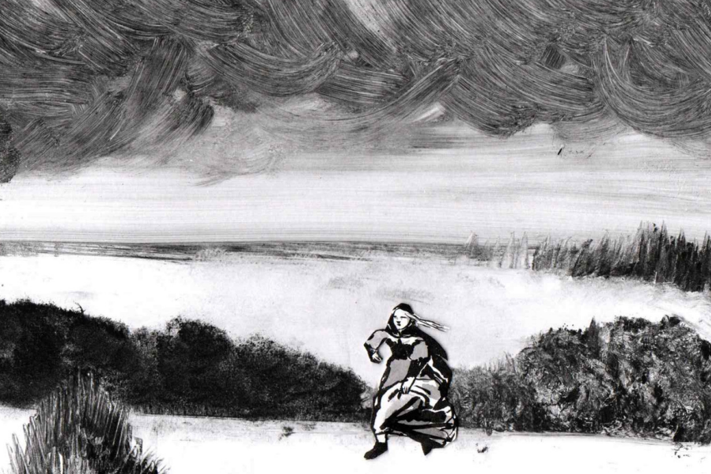

Margarethe Stove’s story and the reforms in Wienhausen exemplify the upheavals in convent life in northern Germany during the Reformation, providing insight into how political, social, and religious conflicts were negotiated within these institutions. This rich backdrop serves as the foundation for a historical narrative that combines fact and storytelling to engage a wider audience. Margarethe’s life is but one of countless stories connected to the Lüneburg convents, yet by focusing on her, we aim to capture the personal dimension of larger historical processes. She embodies the resilience of the women of Wienhausen who fought to preserve their convent and their faith amid overwhelming external pressures. Our graphic novel intends to showcase this exceptional religious and cultural wealth of Wienhausen, particularly through the portrayal of Margarethe’s early years in the convent. In this blog post, we will explore individual steps in Margarethe’s life, enriching her narrative with preliminary artworks for our graphic novel.

Margarete’s story takes you to Northern Germany, specifically to the former Duchy of Lüneburg, now located in today’s Lower Saxony. The area between Lüneburg and Celle is not only home to the Heidschnucke sheep but also the location of the six Lüneburg convents, founded between the 10th and 13th centuries, which continue to exist today as Protestant women’s convents. These include the former Benedictine convents of Ebstorf, Lüne, and Walsrode, as well as the former Cistercian convents of Isenhagen, Medingen, and Wienhausen – the latter being the setting for Margarete’s story.

At the turn of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, the Lüneburg convents faced two significant reforms: first, the Observant reforms influenced by Windesheim and Bursfelde in the 15th century, and then the Lutheran Reformation introduced by the Dukes of Lüneburg in the 16th century. Both were particularly turbulent in the Wienhausen convent.

In 1469, the convent resisted the reform attempts of Duke Otto of Brunswick-Lüneburg. The resistance of the convent was closely tied to the abbess in office since 1422, Katharina von Hoya. During her tenure, a number of significant works of art were created, including the Holy Sepulchre, the so-called Hoya Chalice, and the Salvation Mirror Tapestry. This distinguished and high-ranking abbess was forcibly removed from her position due to the convent’s unwillingness to accept the reform. She was sent, against her will, to the Cistercian convent of Derneburg.

The Wienhausen convent chronicle provides a vivid account of these dramatic events: “When the Duke saw that she [Abbess Katharina von Hoya] could not be won over, he angrily took the keys to the abbey from her and removed her from office. He then had her, along with the cellarer, placed on a wagon and hurriedly taken to Derneburg without the convent’s prior knowledge. […] After the abbess and her cellarer were so pitifully taken to Derneburg, the other virgins who held special offices in the convent were gradually lured out with cunning and sent elsewhere.“

Replacing the convent’s leadership was a method already tested in other convents to successfully implement reforms and proved effective in Wienhausen as well. The convent eventually elected Susanne Potstock, a nun from Derneburg, as the successor to the deposed abbess. Under her leadership, the Wienhausen nuns actively engaged in spreading the reform, for example by participating in the reform of the neighboring Medingen convent in 1479.

Since its foundation by Duchess Agnes of Landsberg (1192/1193-1266), Wienhausen had been at the center of tensions between the Dukes of Lüneburg and the Bishops of Hildesheim, both of whom sought to assert their influence over this regionally significant convent. The same applies to the local nobility of the principality, which had considerable dynastic, political, and economic interests in Wienhausen and the other convents. While no convent membership lists from the period have survived, it is likely that most members of the convent came from families of lower nobility or prominent families from nearby cities such as Celle, Lüneburg, Uelzen, and Brunswick.

Margarethe Stove, the protagonist of our story, also came from a bourgeois family in the nearby residence town of Celle. Our knowledge of Margarethe is primarily based on the Wienhausen chronicle and just three additional documents.

Margarethe was born around 1506 as the daughter of Hans Stove, a merchant and member of the Celle city council, and his wife, Hilke. Margarethe’s entry into the Wienhausen convent was a significant social advancement, as membership in the convent brought with it a lifestyle of relative security and prestige. At the same time, this decision by her family also reflected the importance of the convent as a spiritual and social institution in the region.

It is not known when Margarethe entered the convent. Her ‘career’ within the Wienhausen convent is not well-documented. We only know a few steps. For example, she had not yet taken her vows by 1529 as a letter from Duke Ernst to the abbess of Wienhausen, ordering her to expel all novices from the convent, informs us. This was part of the Duke’s Reformation policies, which sought to reduce the convent’s membership and dissolve it in the long term. However, Margarethe seems to have managed to stay despite the Duke’s direct intervention.

Through her life in the convent, Margarete would have became familiar with the devotional practices of Wienhausen. She likely admired the frescoes in the nuns’ choir that were created around 1330 and, according to the Wienhausen monastic chronicle, were refreshed in 1488 during the monastic reform by three nuns, all named Gertrud.

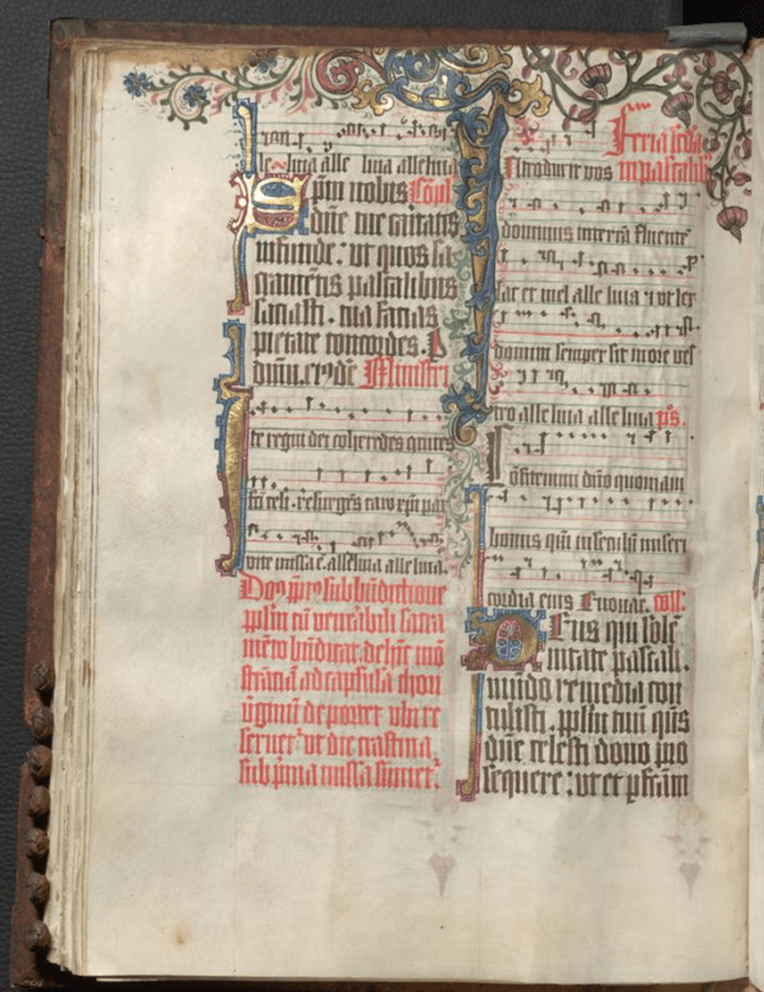

Here, Margarete participated in the Divine Office and the Mass. It is not inconceivable that Margarete observed one or another older nun during her education, whose eyesight had declined with age, necessitating the use of glasses to read the required texts. Of course, we let our imagination roam a bit here, but we weave Margarete’s story around specific items from the monastery’s inventory. During restoration work in 1953, alongside several fragments, the oldest surviving reading glasses in the world were discovered beneath the wooden floorboards of the Wienhausen nuns’ choir. These glasses date back to 1340 and are crafted from wood. Along with more than 100 other items, this discovery became known as the ‘find from the nuns’ choir’ in research. Among the items were several thin booklets containing short devotional texts intended for use in the nuns’ choir—essentially, a kind of “medieval cheat sheet” that Margarete may have carried to ensure she didn’t forget a text. These booklets complement the manuscript heritage of Wienhausen, which also includes the Wienhausen Songbook, a practical manuscript created around 1500 that contains, in addition to a prose piece and a fragment of a letter, 59 songs that Margarete likely knew.

The Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg also preserves a fragment of an elaborately produced complete missal (Hs 7059), which serves as a testament to the grandeur of the former manuscript production at the Wienhausen convent.

It is possible that Margarete also assisted in dressing and undressing the figures and sculptures within the convent—a time-honored practice evidenced today by 17 remaining so-called “Holy Dresses” Along with other decorations such as crowns or chains, these figures were often donated by the parents of the nuns, perhaps including Margarete’s father, Johann Stove.

As idyllic as this may appear, Margarete’s education was soon confronted with the changing religious-political realities. From 1527, Duke Ernst introduced Lutheran Reformation in the principality. In 1528, Provost Heinrich von Cramm voluntarily relinquished the provostship to the duke and placed himself in his service. In the summer of 1529, the duke undertook a visitation tour and assumed control of the provostships in other monasteries, appointing officers and Lutheran preachers there and in Wienhausen. As a result, Duke Ernst suddenly gained access to most of the monastic wealth and gained control over the spiritual and worldly provisions of the convents, which lost their most important advocates in the provosts.

The Wienhausen nuns complained about the maintenance granted to them by the duke in a document dated November 1530, stating that the support was insufficient, as it was based on the tenure of Heinrich von Cramm, who had always provided too little for the monastery for the reasons already mentioned. A particular thorn in the nuns’ side was the newly appointed preacher, a former monk, and the sub-procurator appointed by the previous provost, who literally harassed the women. These somewhat technical remarks should not obscure how dramatically the introduction of the Reformation unfolded in Wienhausen.

The abduction of the Duchess Apollonia of Braunschweig-Lüneburg (1499-1571) from the convent in 1527, vividly described in the Wienhausen monastery chronicle, was an event that Margarete, who had already lived in the Wienhausen convent for five years at that time, likely witnessed firsthand. Apollonia was lured out of the convent under false pretenses, with the provost’s assistance, and taken to Celle. There, her brothers and mother unsuccessfully tried to convince her to renounce her vows and adopt the Lutheran faith. Her pleas to return to Wienhausen were equally unavailing, as were the entreaties of the Abbess. Together with her mother and another former nun from Wienhausen, now married to a former monk, she traveled to relatives in Kur-Sachsen and did not return for years. However, she remained connected to Wienhausen, as several surviving letters with the convent and monastic garments found in her estate testify.

The abduction of Apollonia must have been a traumatic event for the convent in Wienhausen; however, the Wienhausen chronicle further reports that soon, other families followed the duchess’s example, forcibly removing their family members from the convents against the will of the women. This was also the case with Margarete’s parents—but how did this change occur within a few short years?

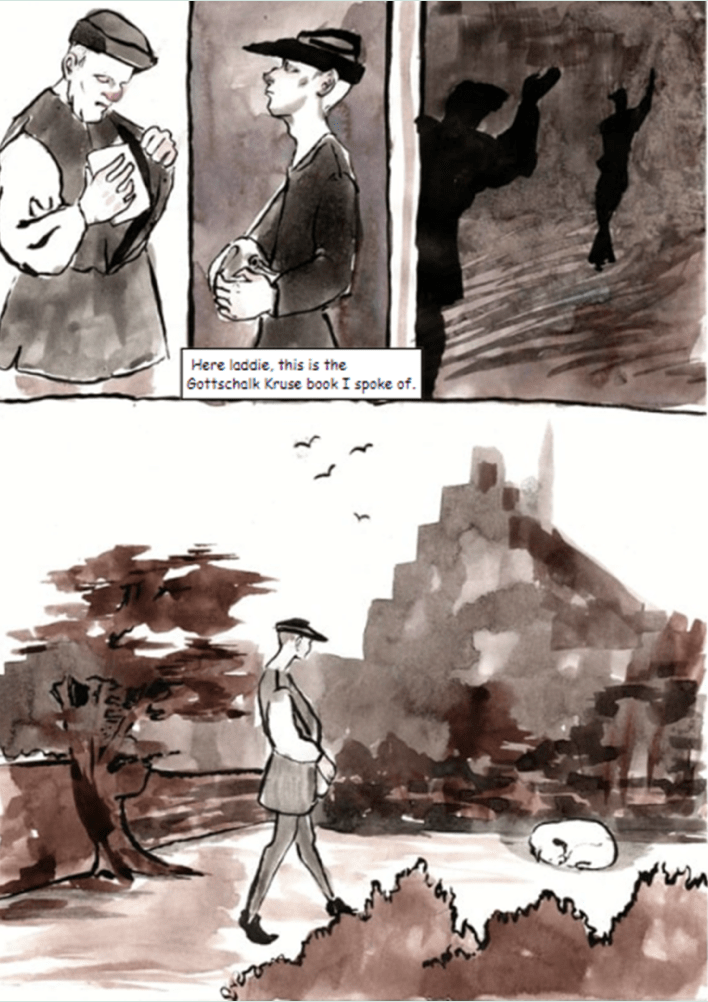

To understand this, it is worthwhile to take a glimpse at the Lutheran publications of the time: Since the early 1520s, not only had works from Luther circulated regarding vows or reasons why women could and perhaps even should be removed from their convents, but also a number of monks and nuns had “fled” from their monasteries, subsequently justifying their decision in publications and encouraging others to do the same. One such publicly active former monk was Gottschalk Kruse (1499-1540), whom the dukes appointed as a preacher in Celle since 1524. It is possible that Margarete’s parents were among his audience. In several reformist writings, the authors directly addressed the parents of nuns and monks. Another influential author was Johannes Bugenhagen (1485-1558). In his writings, referred to monasteries in a 1529 publication not as houses of God but as whorehouses of the devil, into which parents pushed their often young and impressionable children. As a result, they should have feared God’s judgment for this blasphemy.

Therefore, on November 25, 1529, Margarethe Stove’s mother actually came to Wienhausen and attempted to trick her daughter into escaping through the window of the guest house. The nuns and Abbess Katharina Remstede, who had been alerted by Margarete’s screams, were threatened by her, stating she intended to create such a scandal for the convent with the duke that it would be difficult for them to recover from it.

Out of fear of this threat, the Abbess allowed the mother to leave with Margarete and another maiden as a companion, hoping they would return within a few days. However, only the other maiden returned after three days. Margarete’s parents continued to try to pry their daughter away from convent life, ultimately taking her monastic wreath and habit. Yet Margarete did not let herself be discouraged.

One day, while her parents were still sleeping, as the monastic chronicle recounts, she fled back to the convent. Faced with the locked gates, she waded through the Aller River, which flows past the convent, and appeared unexpectedly before the choir, where she was joyfully welcomed by the community. They prayed together before the altar and in the chapel in front of the holy crucifix, thanking God for His help. In front of the assembled convent, the Abbess clothed Margarete anew in religious garments.

However, a return to normalcy was not possible even after this. When rumors arose that her parents planned to forcibly remove their daughter again, Margarete was sent on October 28, 1531, to the St. Magdalene Convent in Hildesheim. She spent nearly four years there, during which she occasionally visited Wienhausen when the opportunity was safe. It was not until her professing and consecration, as described at the beginning, that she finally returned to Wienhausen for good.

Concurrently with Margarete, Abbess Katharina Remstede was likely also in exile at the Hildesheim Magdalene Convent. The duke, repeatedly—among other means with the help of the former provost—attempted to obtain the convent’s letters, seals, and treasures. However, the convent and the Abbess steadfastly refused these demands and also rejected the idea of listening to Lutheran sermons or relinquishing their traditional ceremonies. Katharina von Remstede maintained close contact with her counterparts in other convents, evidenced by the letters archive from the Lüne convent that still exists today. She is said to have even written a theological treatise against the Lutherans in 1530, although this has not survived.

In 1531, the situation finally escalated: Upon returning from a trip to Braunschweig, the Abbess was detained by ducal men and held captive in a cellar for 12 days. After her release, she fled with the letters, seals, and treasures to Hildesheim—meanwhile, the duke ordered a quarter of the convent to be destroyed, including almost all the chapels and the convent walls. This breached enclosure ultimately contributed to the circumstances mentioned at the beginning, where an unknown Lutheran was able to observe Margarethe’s clandestine profession in the choir. Further ducal visitations followed, along with confrontations in the nuns’ choir, and even theological writings addressed to the Wienhausen convent, such as Urbanus Rhegius’s (1489-1541) directive on why the nuns should discontinue singing “Salve Regina.”

Nevertheless, the nuns persisted in their resistance for decades. Margarete Stove only appears once more in the historical records after the dramatic events surrounding her abduction, flight, exile, and ultimately her profession: During a ducal visitation and confessional inventory of the convent in March 1570—40 years after her abduction and return to the convent—her name was not listed among the 15 women still regarded as papist; apparently, Margarete had since consented to receive the Eucharist in both kinds. However, she seems to have remained closely connected to her convent’s traditions; it is not only attributed to the entire convent but also to Margarete’s influence as a prioress and friend that the former Lutheran novice Anna Freytag, after eight years in the convent, was now considered somewhat papist by the duke and his advisors.

Confessional ambiguity is typical for Wienhausen and other convents in the principality during the 16th century, as it was extremely difficult for Lutheran reformers to categorize nuns confessionally. The most important criterion was their stance on the Eucharist. However, examples like Margarete and her pupil illustrate how complex the relationship between Lutheran confession and monastic tradition was, even for contemporaries. Wienhausen received its first abbess in 1587, who received the Eucharist in both kinds. However, the nuns did not officially abandon the Cistercian habit until 1610, continued the convent necrology until the 1620s, and ceased singing Latin choral pieces only in 1619. Therefore, the transformation of Wienhausen and the other Lüneburg female convents into Lutheran institutions was a long and gradual process.

Margarethe Stove’s story and the reforms in Wienhausen exemplify the upheavals in convent life in northern Germany during the Reformation. The convents were places where political, social, and religious conflicts were negotiated in microcosm. These tensions provide a rich background for a historical narrative that combines fact and storytelling to reach a wider audience. The story of Margarethe Stove is just one example of the countless life stories connected to the Lüneburg convents. By focusing on her, we aim to capture the personal dimension of larger historical processes. Margarethe represents the women of Wienhausen who fought for the preservation of their convent and their faith in the face of overwhelming external pressures.

Leave a comment